Dr Karen Attar, Rare Books Librarian at Senate House Library and author of numerous articles about the Library and its holdings, talks about the Library’s recently published volume of treasures.

(see Senate House Library, University of London, ed. by Christopher Pressler and Karen Attar (London: Scala, 2012) View on Copac)

In November 2012 Senate House Library, University of London, produced a treasures volume featuring a brief history of the Library and sixty highlights from its special collections. The publication is a landmark. The treasures volume is by no means the first publication to appear about Senate House Library. Its first catalogue was published in 1876, the year before the Library opened. Numerous catalogues have followed, culminating in the five-volume short-title Catalogue of the Goldsmiths’ Library of Economic Literature (1970-1995), which has provided a standard for economic completeness (viz. “Not in Goldsmiths’” in booksellers’ catalogues). Articles about specific collections or groups of collections have appeared in various academic journals. But the treasures volume published by Scala is the first large-scale publication with lavish illustrations intended for a general audience.

Senate House Library opened as the University of London Library in 1877. Donations had dribbled in from 1838 onwards. The impetus for a University Library came with the acquisition of the University’s first purpose-built accommodation in Burlington Gardens, Piccadilly, in 1870, with a large ground-floor room to double as an examination hall and library. No sooner had the Chancellor appealed for books to fill its empty shelves than Samuel Loyd, Baron Overstone, purchased and gave the library of the recently deceased mathematician and mathematical historian Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871). This comprised over 3,500 titles, mainly to do with the various branches of mathematics (including astronomy) and its history: a collection which was praised at the time and which, over 120 years later in 1996, Adrian Rice called ‘one of the finest accumulations of books on the history of mathematics in the country’.

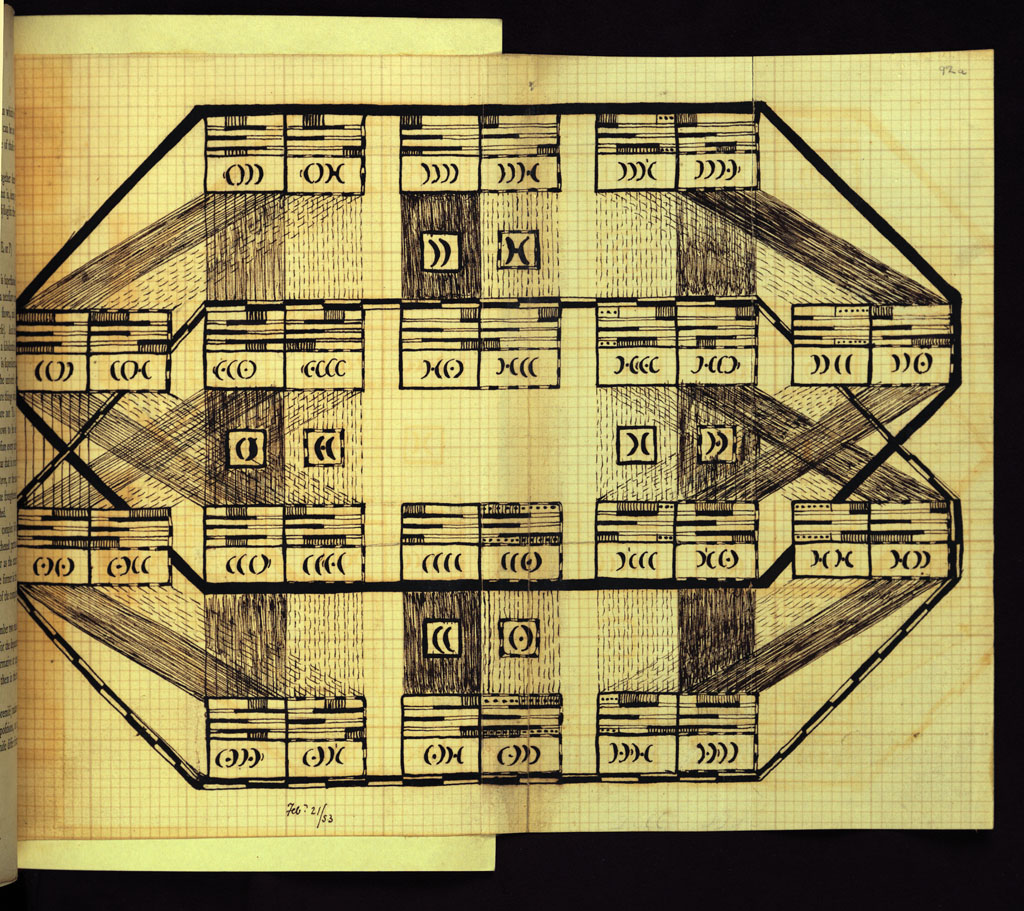

Obvious treasures included the first five printed editions of Euclid, first editions of Newton’s Principia and Opticks, and the first edition of Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus, this last individualised by De Mogan’s annotations; also noteworthy were runs of popular textbooks, such as Cocker’s Arithmetic and Francis Walkingame’s The Tutor’s Assistant. De Morgan’s notes, often humorous and sometimes shedding light on the history of mathematics, enhanced a significant minority of the books: a feature noted as adding to their value even at the time of De Morgan’s death, and one which has gained significance in recent years with the general boom in the history of reading and provenance research. The collection was catalogued online, with help from the Vice-Chancellor’s Development Fund of the University of London, in 2004-6. The iconic 1482 editio princeps of Euclid’s Elements is by no means a rare book, with 41 copies recorded on the ISTC for the British Isles alone and many more across the world; and De Morgan’s copy of the first edition of Copernicus has received prominence elsewhere, as in David Pearson’s Books as History (2008). For the treasures volume, we therefore regarded these as out of bounds. De Morgan’s own extensive writings included an article ‘On the Earliest Printed Almanacs’ in The Companion to the Almanac for 1845 and a separate monograph The Book of Almanacs (1851), and we represented this area of his interest with the first of several early almanacs from his library, the Lunarium ab Anno 1491 ad Annum 1550 by Bernardus de Granollachs (ISTC ig00340700). An added attraction to featuring this work is that De Morgan’s is the only complete copy known. We featured De Morgan’s copy of his Formal Logic(1847): interleaved and bound in two volumes, it is full of scribbled notes, newspaper articles and personal letters, with some unpublished diagrams which show his mind at work.

Arithmetic was a major focus of his collecting and there would have been numerous early printed books from which to choose. Ultimately we selected a late edition of John Bonnycastle’s The Scholar’s Guide to Arithmetic, edited by retired schoolmaster Edwin Colman Tyson (1828). This is a prime example of how small, common textbooks are prone to disappear: the Senate House Library copy is one of only two on Copac. De Morgan’s copy includes his note from 1857: “This book was sent to me by the publisher, meaning to call my attention to it as a class book. It convinced me that a work on demonstrative arithmetic was wanting – and was the book which suggested the existence of the deficiency to supply which I wrote my own arithmetic in 1830” – what a devastating verdict by an experienced and dismissive reviewer!

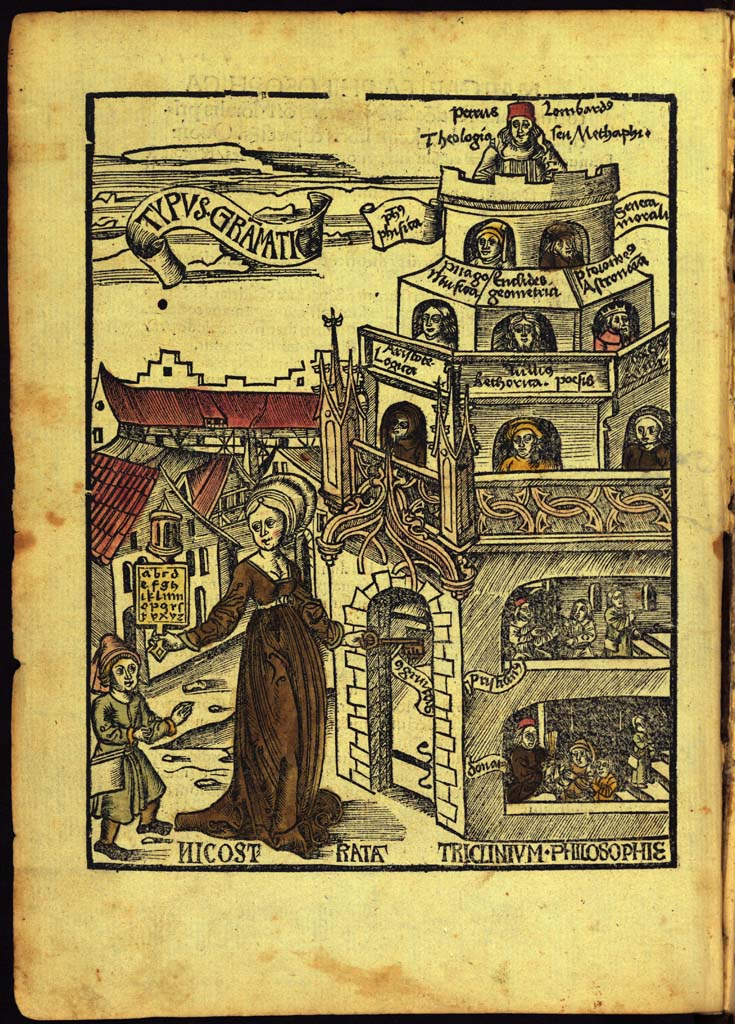

Classical historian and University of London Vice-Chancellor George Grote died on 18 June 1871, just four months after De Morgan. Grote bequeathed his books to the University. Unlike De Morgan, Grote had not been a conscious collector. But he had been a voracious reader, with money from 1830 onwards to satisfy his wide-ranging literary interests, and his library contained about five thousand titles. Director’s Choice, by Christopher Pressler – our Director’s selection of thirty favourite items from the collections –had come out a few months earlier and snaffled Grote’s collection of French Revolutionary pamphlets, comprising some items which were not only very rare (again, because they were ephemeral) but which epitomised an area of Grote’s interest: according to his 1962 biographer, Martin Lowther Clarke, he was thought to have read everything there was to read about the French Revolution. We made do with the French translation (rare in Britian; the only other copy on Copac is at the British Library) of Grote’s History of Greece and with the second-oldest item in his collection, Gregor Reisch’s Margarita Philosophica (1504), in a copy including some hand-colouring and in a contemporary blind-tooled calf binding.

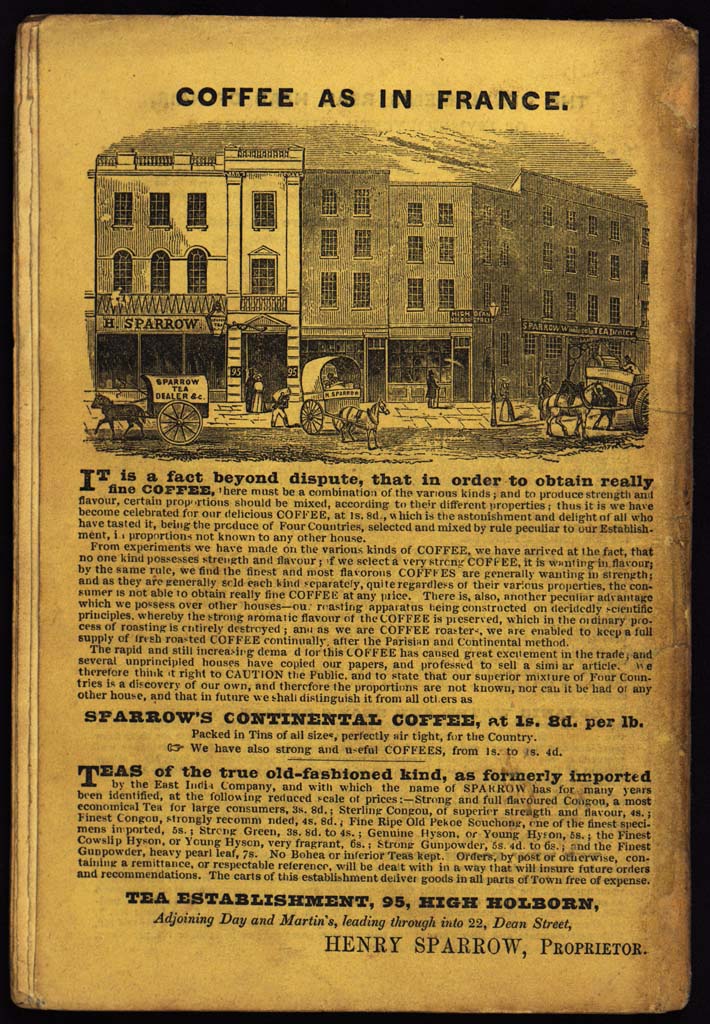

It was the gift of the Goldsmiths’ Library of Economic Literature in 1903 – some 30,000 items – which doubled library holdings and transformed the University Library into a major academic institution. Director’s Choice had already claimed the Collection’s most outstanding item in terms of provenance, a copy of Das Kapital (1872) inscribed by Marx to Peter Imandt (1823-1897), a fellow political émigré and German teacher in Dundee who worked with Marx and Engels for many years after having arrived in London, via Switzerland, in 1852. In the treasures volume we highlighted the founding item of the Goldsmiths’ Library, Dionyius Lardner’s Railway Economy (1850), annotated by the founder of the library, Herbert Somerton Foxwell: “I bought this volume from a bookstall in Great Portland Street at Jevons’ suggestion, one afternoon as I was going to Hampstead with him, for 6d.! He urged me to buy it, partly on account of the low price, partly because it was a book of great intrinsic value, from which had suggested to him the mathematical treatment of economic theory. [cf. ch xiii] This purchase was the first step in the formation of my economic collection.” In addition to buying Foxwell’s collection and presenting it to the University of London, the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths financed the extension of the collection, such that it is now more than twice the size of the original gift. Our choice of other items from the Goldsmiths’ Library of Economic Literature honoured collection building, with the first printed work on economics (Franciscus de Platea, Opus Restitutionum Usurarum, Excommunicationum, 1472; ISTC ip00751000), and a professional diary of the energetic railway engineer John Urpeth Rastrick (1780-1856).

On the whole the treasures volume follows and acknowledges the receipt of other major special collections to the University, from the Durning-Lawrence Library based around Sir Francis Bacon and the Quick Memorial Library of works on education, both given in 1929, to the M.S. Anderson Collection of Writings on Russia Printed between 1525 and 1917 and editions of Walter de la Mare’s work (given in 2008 and 2009 respectively). But it is important to acknowledge that not all the noteworthy works in a library are held in named special collections, and the treasures volume does this, for example with single purchases or gifts. The most valuable item featured falls into both these categories. It is an illuminated manuscript produced around 1385 chronicling the exploits of Edward, the Black Prince, during the Hundred Years War. Purchased by the University to present to the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) in 1921, it was subsequently placed by him on permanent loan to the University Library. Occasionally the means of acquisition is unknown, as for the short-running journal of the Healthy & Artistic Dress Union Aglaia (recorded on Copac only for Senate House Library and the National Art Library).

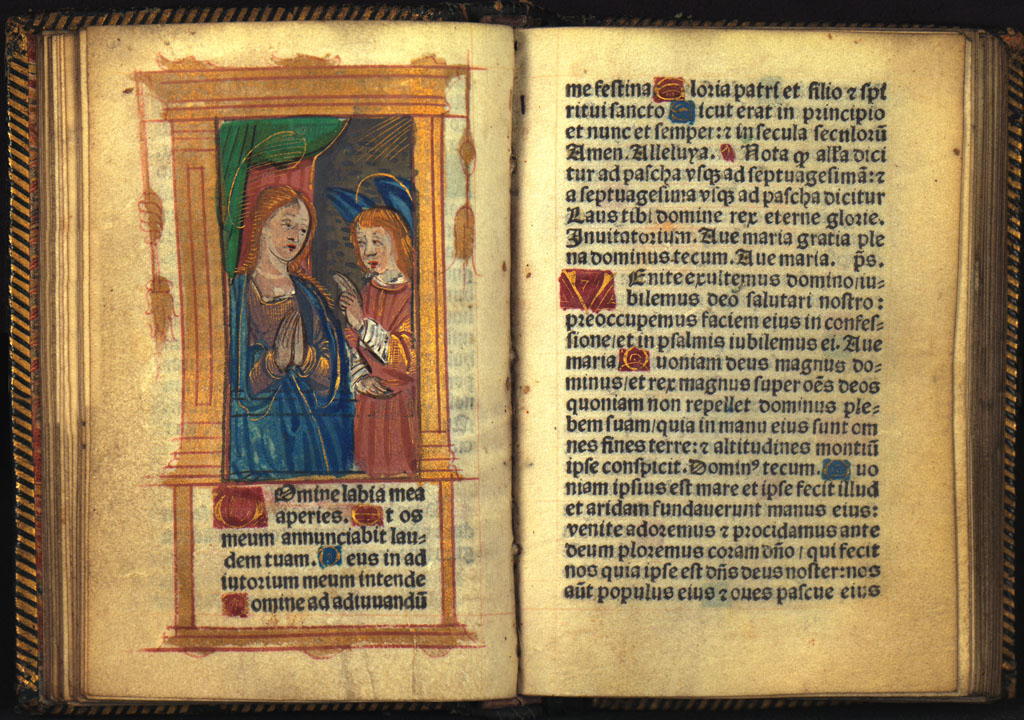

Editing a treasures volume is not conducive to cherishing favourite items, as one’s energies are focused on searching for errors and inconsistencies in drafts. Yet certain items do stand out for particular features. For sheer beauty, my preferred item is a small (110 x 72 mm), apparently unique book of hours printed on vellum in Paris for Germain Hardouyn in about 1516: the book is rubricated and illuminated, with a half-page coloured illustration for each of the hours.

The book I am most curious to read is The Greatest Plague in Life or The Adventures of a Lady in Search of a Good Servant, by the brothers Henry and Augustus Mayhew (1847) – a book reprinted at least three times in the Victorian era, as copies on Copac testify, but which has since sunk into obscurity.The first edition of the book is by no means rare, with copies from twelve libraries on Copac, but Senate House Library is the only library to have recorded ownership of the six original parts, complete with advertisements for pens and ink, iron fenders, lingerie, wigs, and hair dye.

For us there is also a local interest, as the narrator is based in Guildford Street, Russell Square, whence she complains that she has been driven “through a pack of ungrateful, good-for-nothing things called servants, who really do not know when they are well off”. This book promises to rate highly for amusement value, although for the top position in that category it vies with Thomas Carlyle’s acerbic marginalia on the first edition of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh (for example, “don’t!” when the protagonist says it is “too easy to go mad”).

“What and where is the University of London?” is a query which vexed University officials before the central University moved from South Kensington to its current home in Bloomsbury in the 1930s. “What and where is Senate House Library, University of London” albeit not asked so explicitly, has often been implicit. A document from 1946 claimed that the University of London Library was not as well known as it deserved to be, even within the University of London; and half a century later we still encounter researchers who are surprised by the richness of the Library’s holdings. We hope that the treasures volume will stop such a question from being asked at all.

All images copyright Senate House Library, University of London, and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holder.

Categories